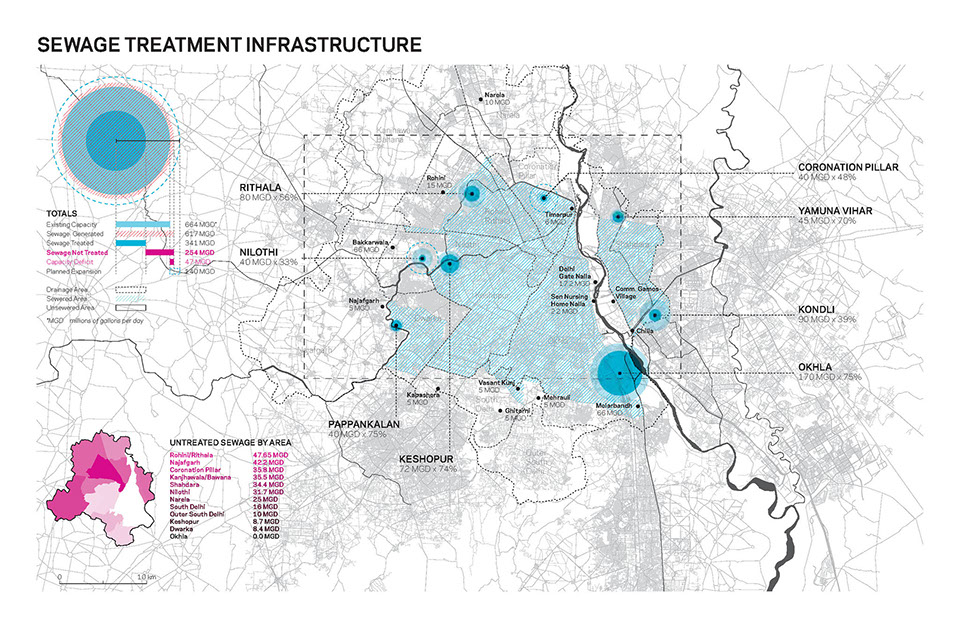

Delhi’s sewage treatment infrastructure has not kept pace with the growth and development of the city. The treatment plants form a ring that used to be on the periphery of the city but has since been engulfed by continued growth. Many districts still lack piped connections to sewer infrastructure, and by the Jal Board’s estimation, the treatment plants are operating at only about 65% of their capacity.

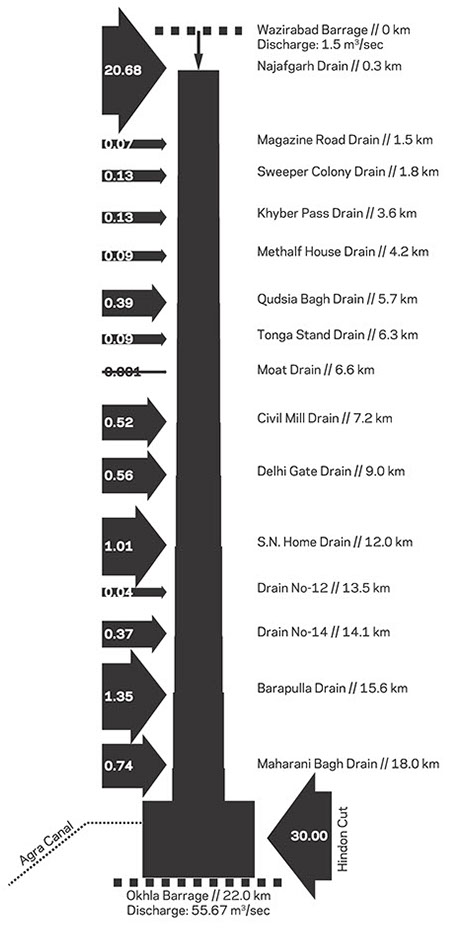

Just north of Delhi, at the Wazirabad Barrage, the clean Himalayan waters of the Yamuna River are almost 100% diverted for use as drinking water. That flow is effectively replaced by the outflow of the Najafgarh Drain, which is massively polluted by a combination of agricultural and industrial runoff, solid waste, and untreated domestic sewage.

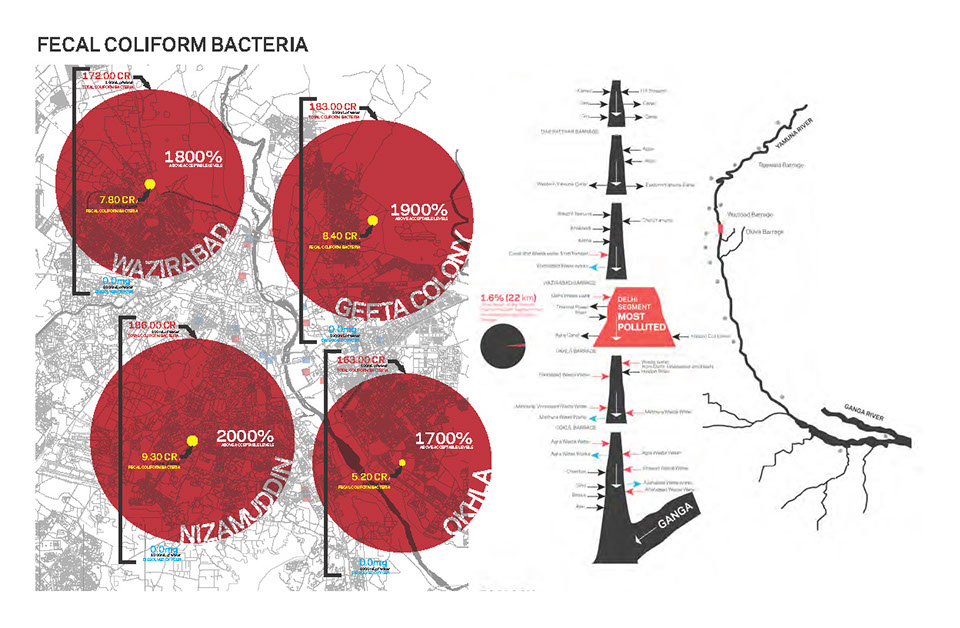

In the dry season, when there is no stormwater to speak of, Delhi’s drainage system functions primarily as an open sewer, leading to fecal coliform bacteria levels that are in some cases up to 2000% above safe standards.

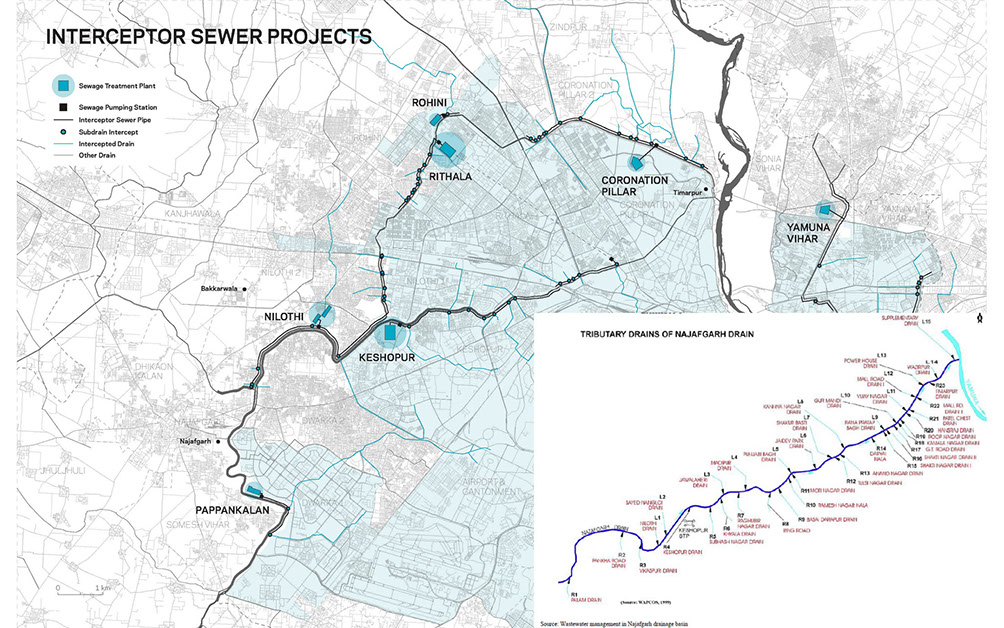

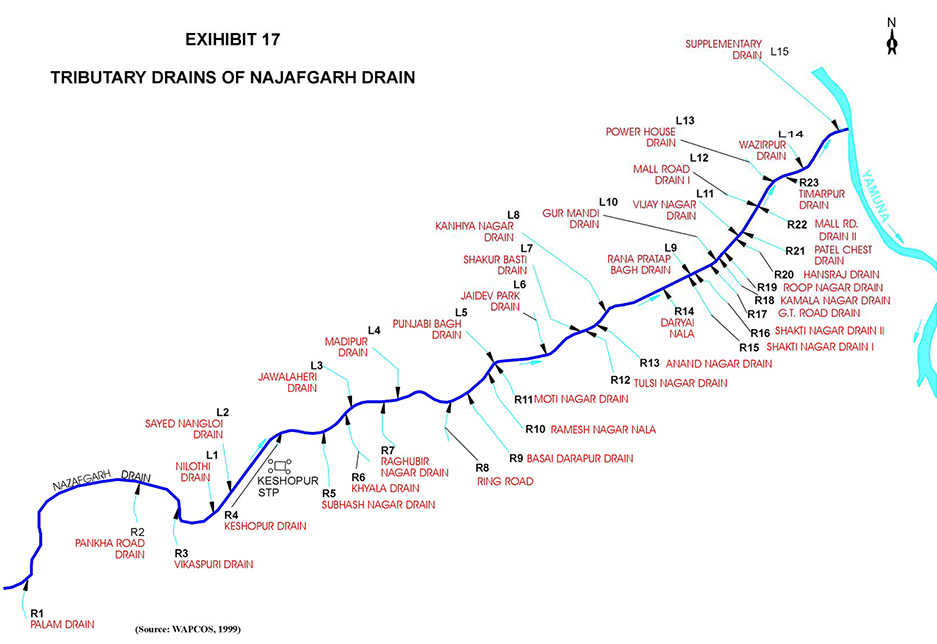

The Jal Board is in the process of taking an important first step, installing a series of “interceptor sewers” which will capture black water in the drain system and divert it to nearby sewage treatment plants. In the first phase, major tributary drains are intercepted.

Moving through Delhi towards the Yamuna, the Najafgarh Drain is the city’s back yard, practically invisible, with no public space, used primarily as a dumping ground and for hard infrastructure. It’s not a place meant for people. Every day, approximately 250 million gallons of raw sewage is dumped into the stormwater drainage system, where it finds its way to the Najafgarh Drain and the Yamuna River.

A complete characterization of Delhi’s urban water can be described by two collocated problems: quality and inequality.