Daylighting the Palam Corridor:

A New Urban Datum for Pedestrian Movement

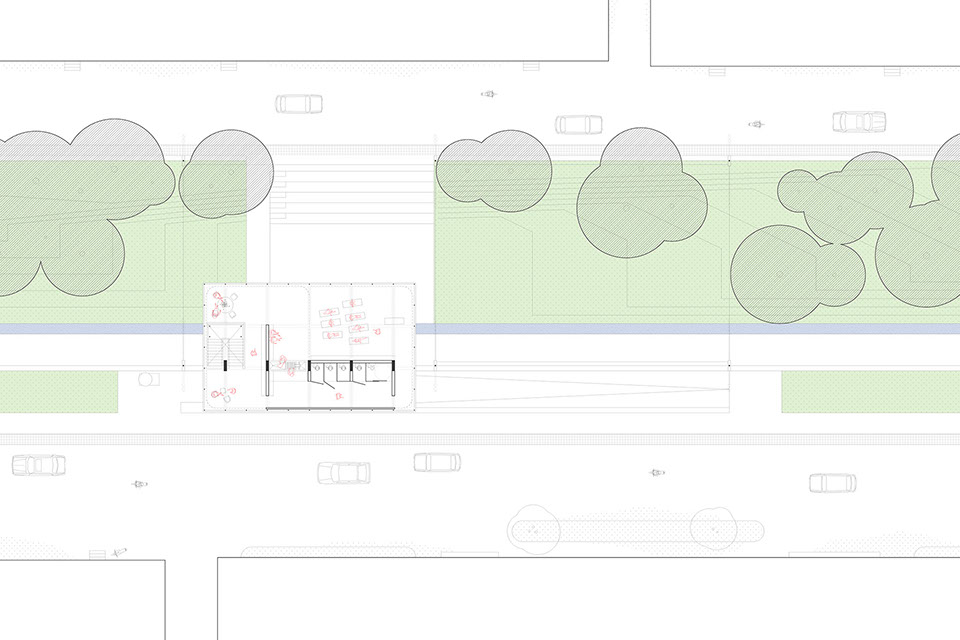

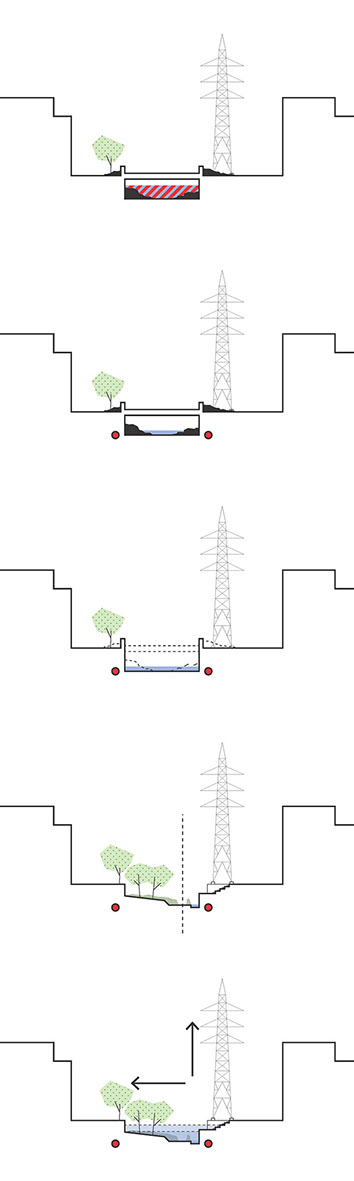

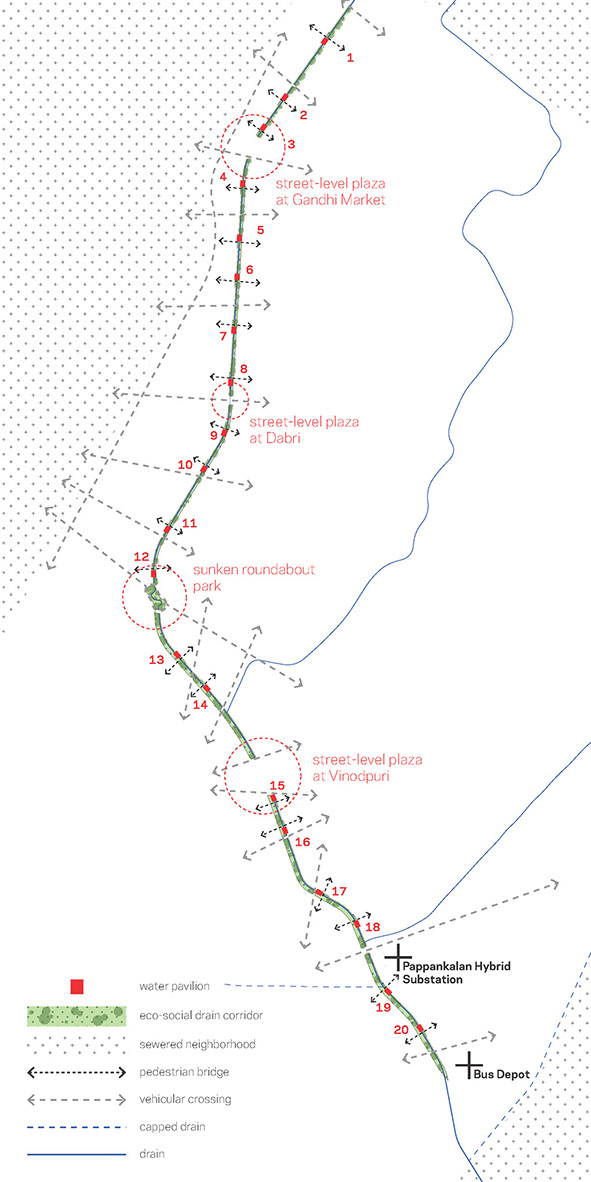

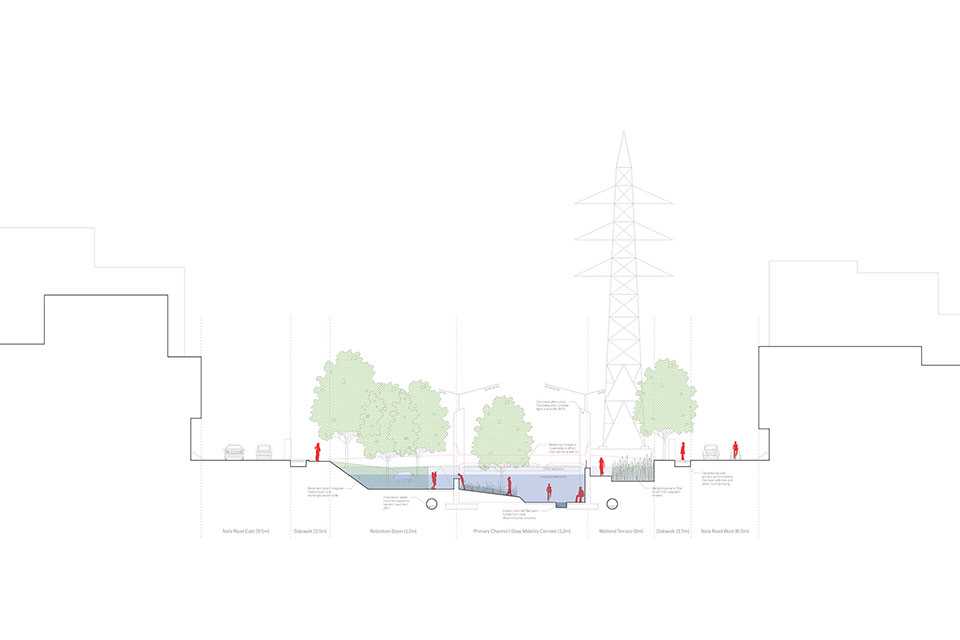

Domestic Water is a pilot project for a system of hydrological and social infrastructures that intensify, rather than attempting to do away with, the Palam Drain’s role as an urban armature. The project daylights the 5-km stretch of the Palam Drain currently capped by a six-lane road, adding landscape-based stormwater treatment systems, pedestrian and bicycle circulation, and a suite of public facilities to a busy corridor that serves a large lower-middle-class population. The project establishes a new system of public space, allows for continuous pedestrian navigation, and makes habitable the city’s infrastructural datum (approximately 4m below street level). It provides a respite from, and a new perspective on, the hyperactivity of a growing global megacity.

Domestic Satellites:

Making Oneself at Home in Public

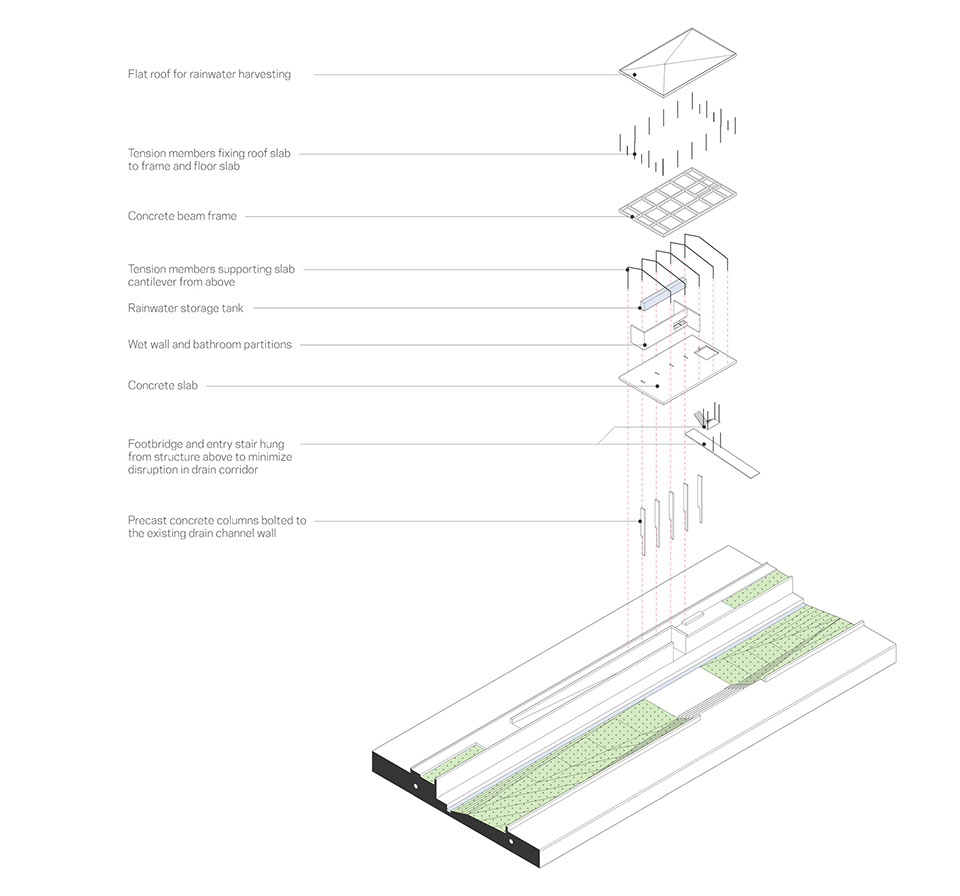

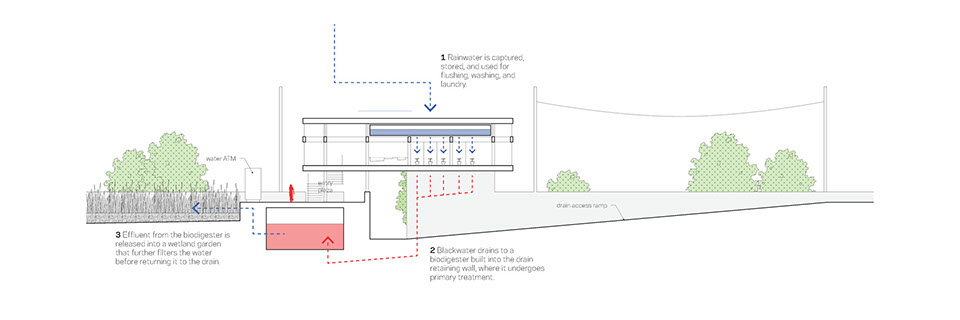

The provision of clean water, and the activities that require it—including cooking, bathing, and using the bathroom—are often exclusively associated with the domestic realm. But in urban contexts such as Delhi, one cannot presume that piped infrastructure will deliver clean water to the interior of the home, nor discreetly remove dirty water from it. Instead, Delhi has developed social practices of procuring, using, and disposing of water in public, blurring the distinction between the domestic and the urban. The architectural component of the Palam Drain daylighting project serves to harness and choreograph this public use of water, extending the domestic realm into the city. A series of twenty pavilions, an average of 200m apart, are built parasitically onto existing maintenance access structures, cantilevering out over the drain to maximize their square footage without impacting the ecological corridor below. The pavilions provide access to clean water in the form of public restrooms, water ATMs, and basins that can be used for washing and laundry. Rainwater harvesting and waste-treatment systems supplement piped connections to hard infrastructure, reducing their burden on the municipal system. And in addition, each pavilion provides approximately 150 square meters of flexible space for small events, classes, and leisure activities

The provision of clean water, and the activities that require it—including cooking, bathing, and using the bathroom—are often exclusively associated with the domestic realm. But in urban contexts such as Delhi, one cannot presume that piped infrastructure will deliver clean water to the interior of the home, nor discreetly remove dirty water from it. Instead, Delhi has developed social practices of procuring, using, and disposing of water in public, blurring the distinction between the domestic and the urban.

In addition, the domestic sphere has in many cultures been constructed as a womens’ space, in contrast to the public realm, which is largely made for and by men. In Delhi this division is still felt acutely, in the culture of “Eve teasing” and in the recent spate of high-profile cases in which women have been attacked or sexually assaulted in public. And lest we think this has little to do with the question of clean water, access to safe and sanitary toilet facilities has been a recent focus.

The architectural component of the Palam Drain thus serves to extend the domestic realm into the city in two ways. A series of twenty pavilions, built parasitically onto existing maintenance access structures, provides clean water in the form of public restrooms, water ATMs, and basins that can be used for washing and laundry. In addition, each pavilion provides approximately 150 square meters of flexible space for small performances, classes, and leisure activities. And the possibility of single-sex domestic satellites means that this project could serve to create a network of safe public spaces that women can domesticate for themselves.