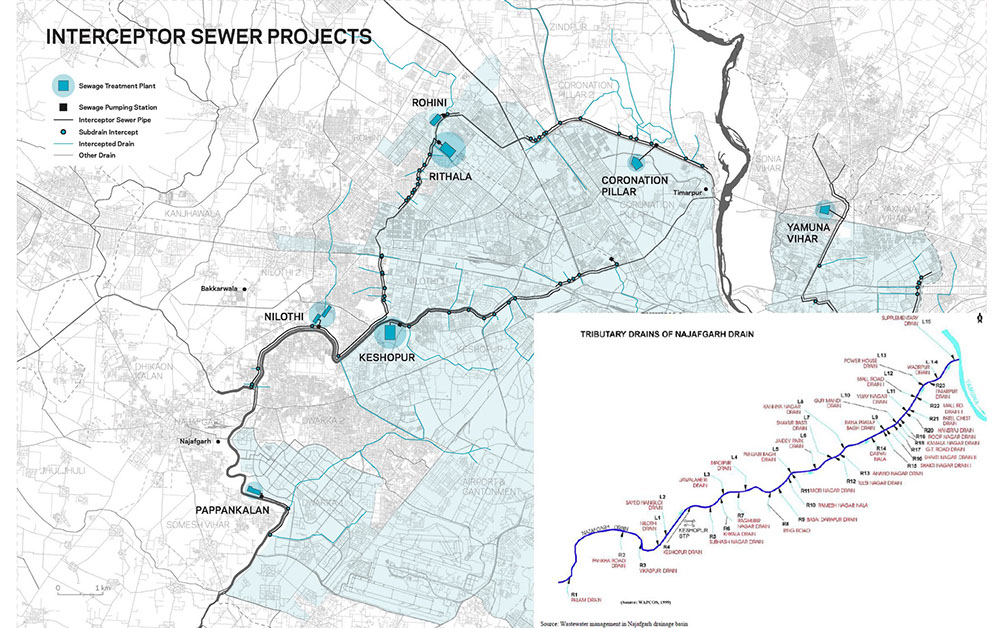

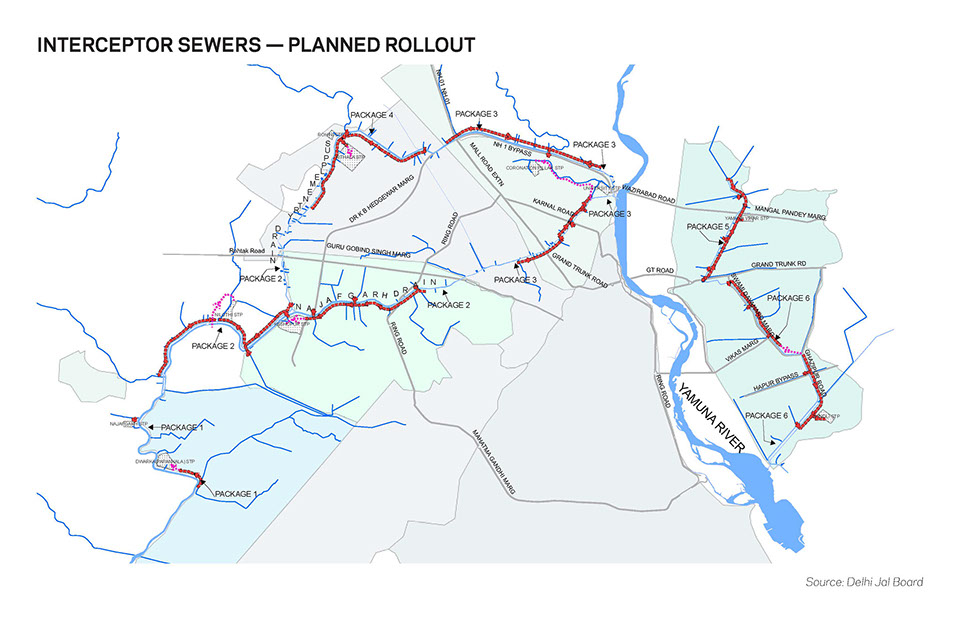

The Delhi Jal Board is in the process of implementing interceptor sewers across the city, including 78 tributary drains that flow into the Najafgarh Drain.

The areas east of the Yamuna River and west along the Najafgarh Drain have the highest population density. This trend in density directly correlates to pollution of the water bodies. The average population density is 11,050 people/sq. km. in Delhi, in comparison to 2,050 people/sq. km. in New York City, or 3,550 people/sq. km. in Paris, France.

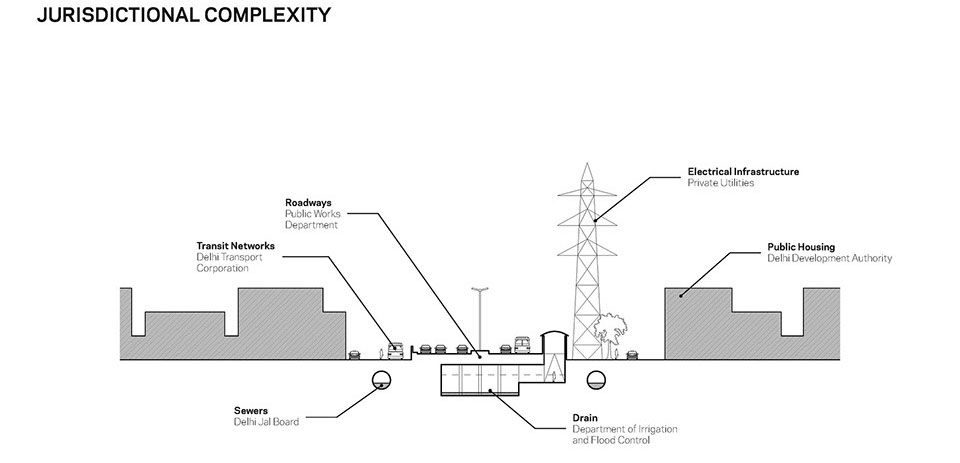

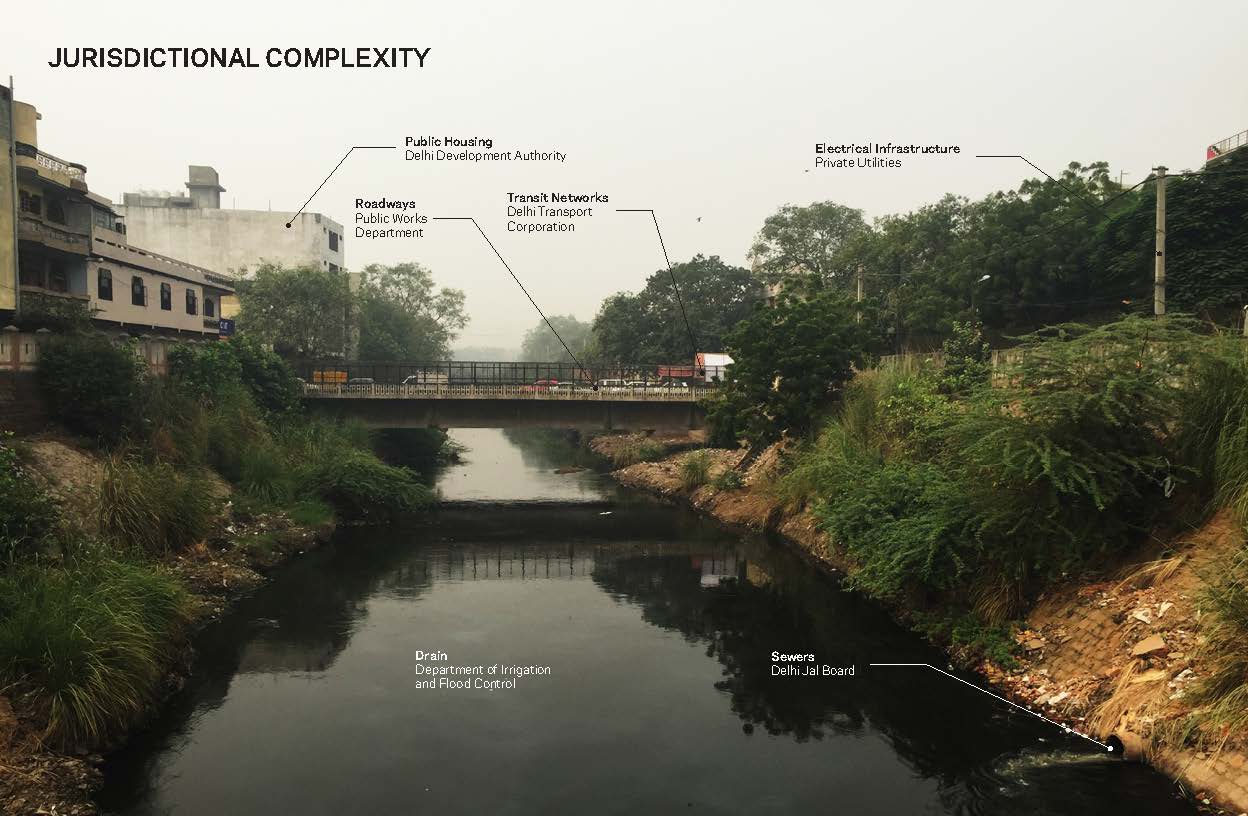

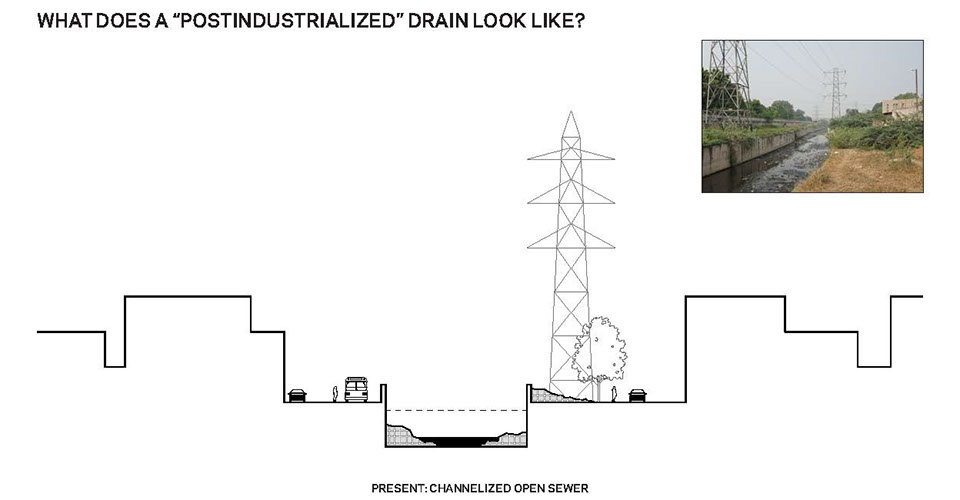

Delhi’s urban waterways are contested territories that serve as corridors for multiple infrastructures. As such, they are sites of intense juxtapositions of jurisdiction and authority. Working in a typical drain corridor can involve coordinating with up to six separate municipal agencies and private interests.

The Delhi Jal Board is in charge all the piped sewage infrastructure in the city, but the drains themselves fall under the jurisdiction of the Irrigation and Flood Control department, despite the fact that they essentially function as open sewers. Through efforts to bring the Irrigation and Flood Control department under the authority of the Delhi Jal Board, this should help create an institutional and policy framework that will allow for a holistic approach to Delhi’s socioecological dilemmas.

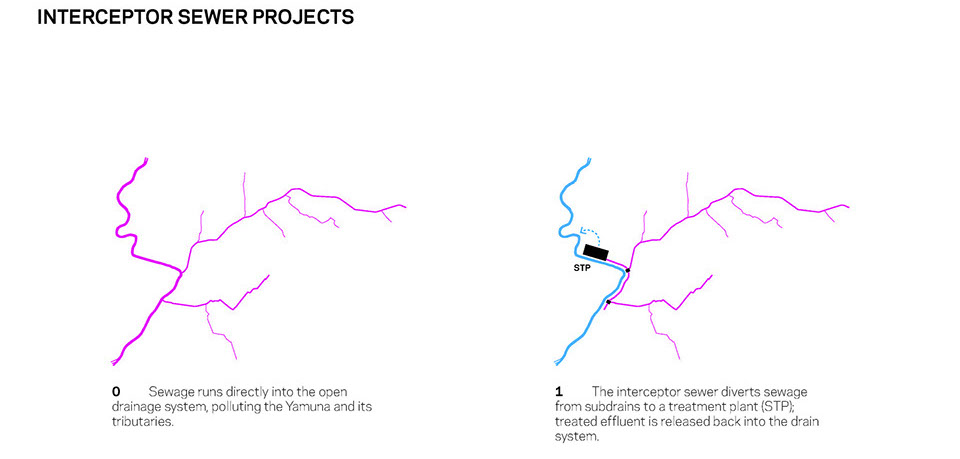

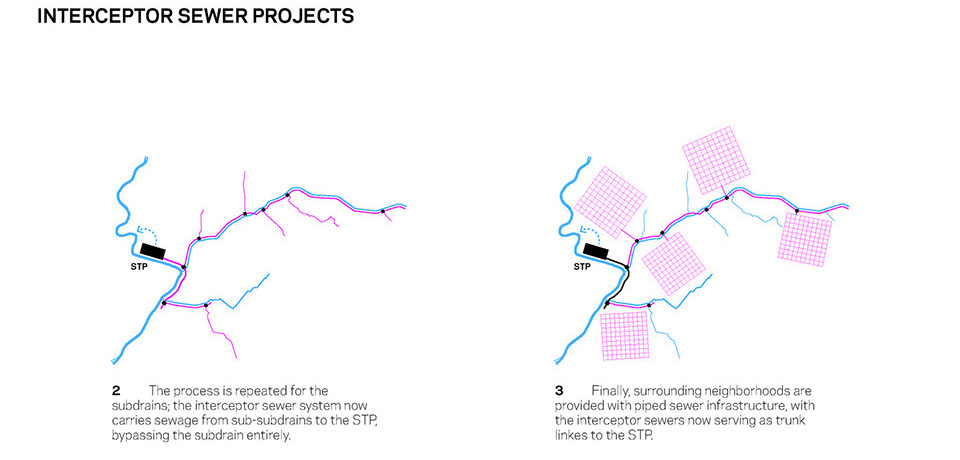

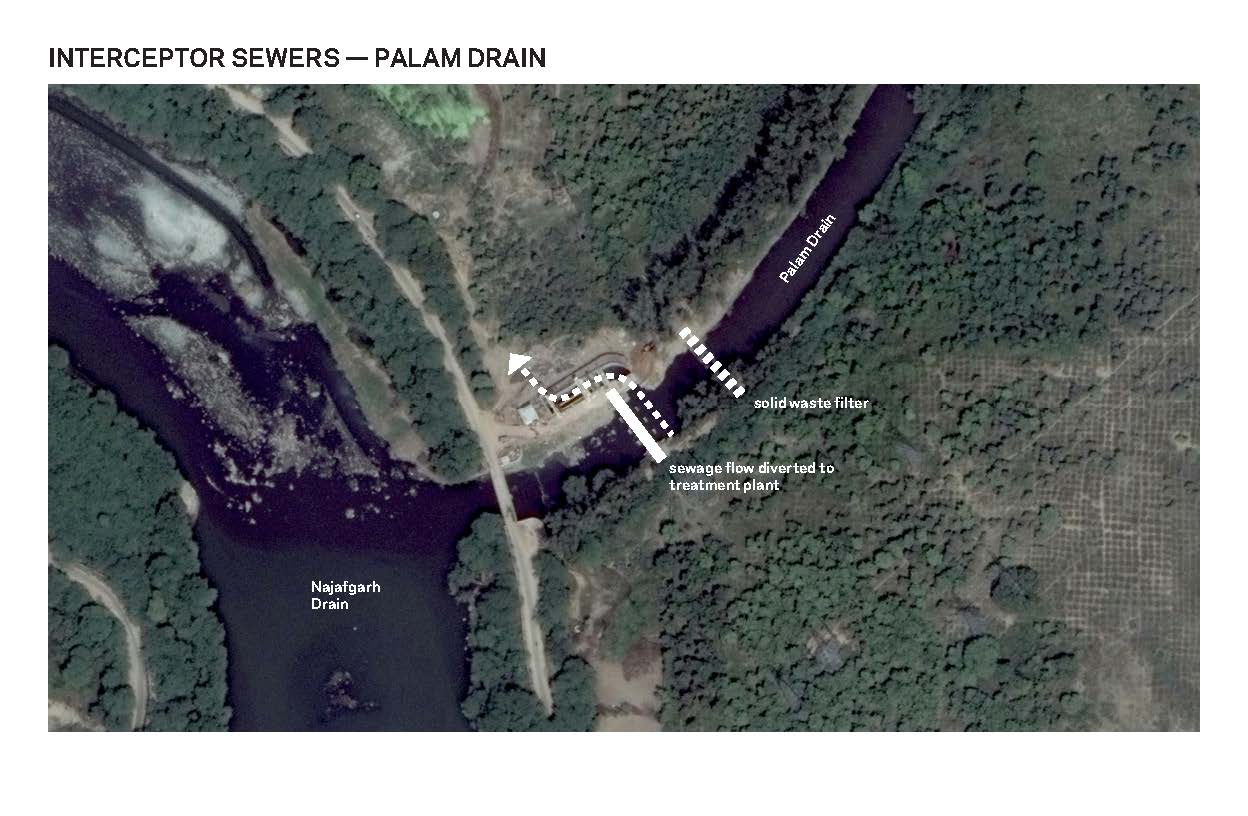

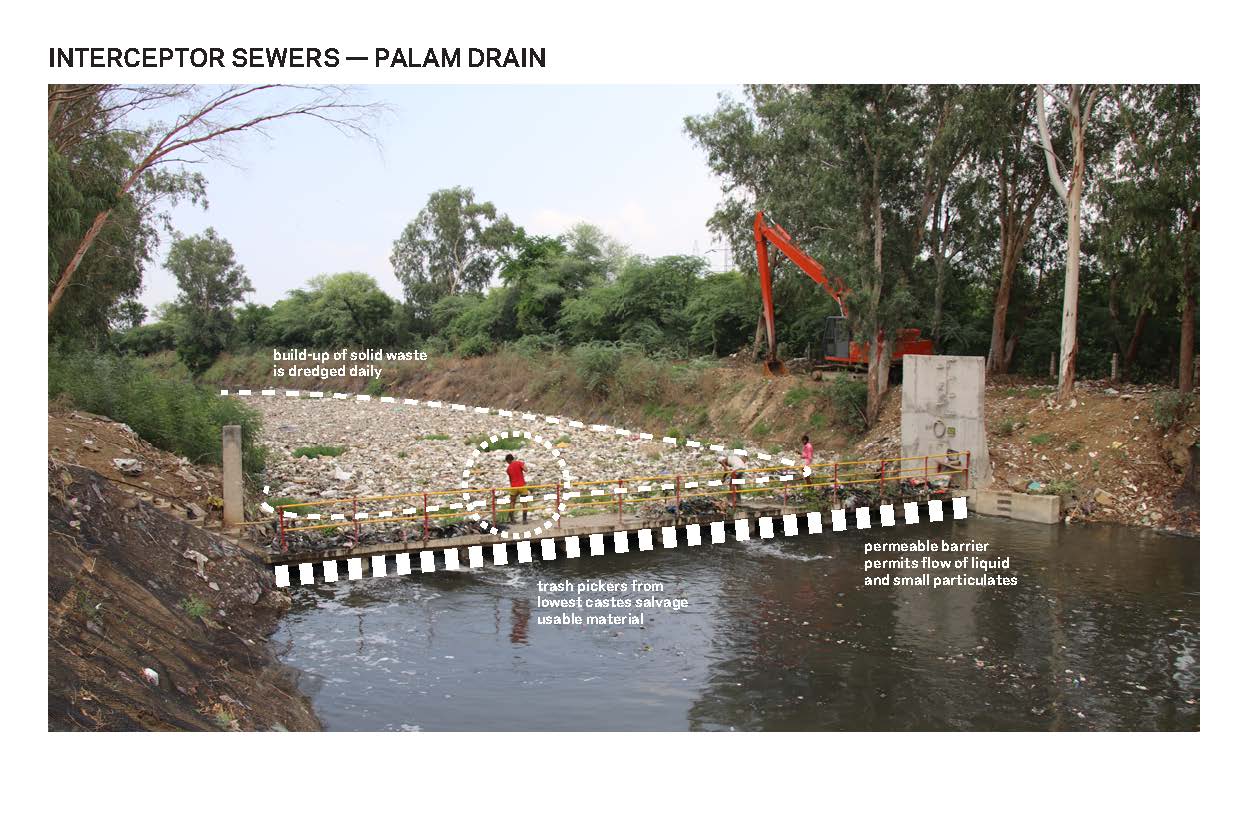

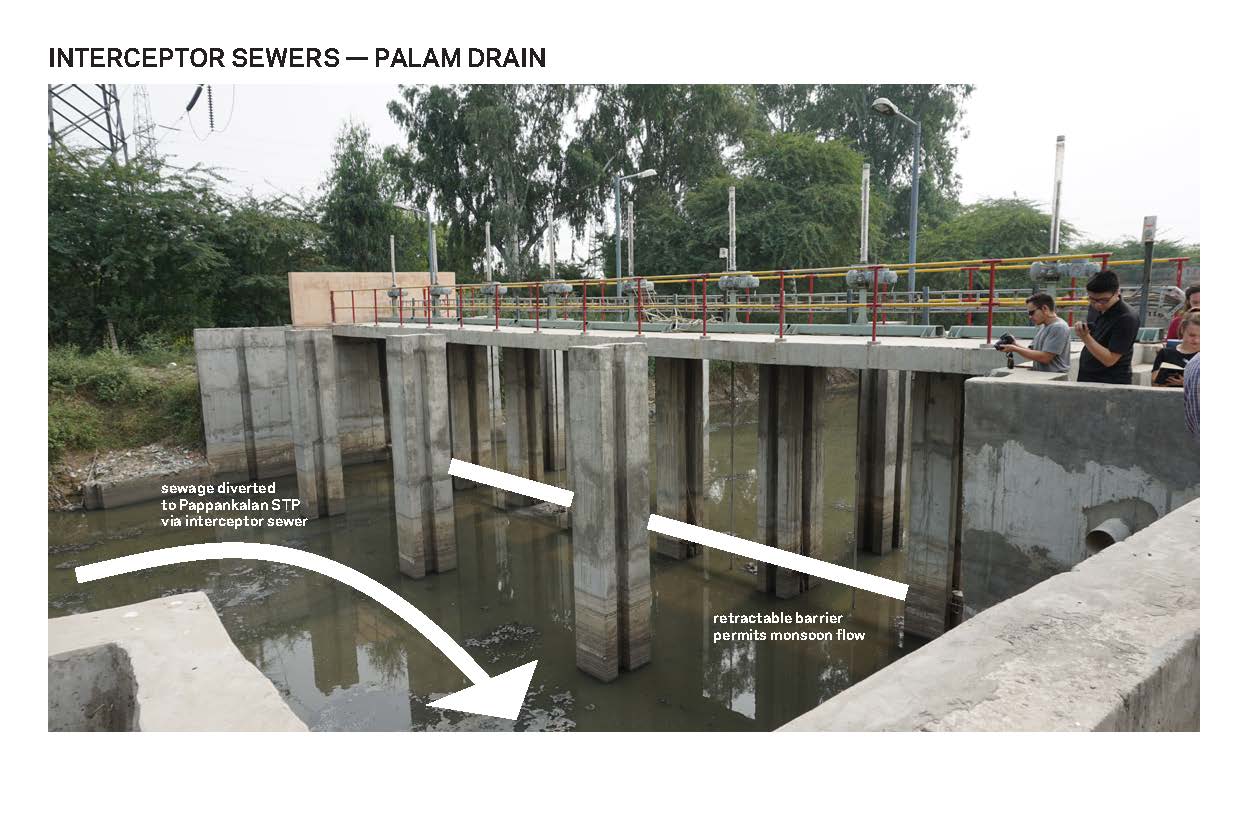

The Jal Board is in the process of taking an important first step, installing a series of “interceptor sewers” which will capture black water in the drain system and divert it to nearby sewage treatment plants. In the first phase, major tributary drains are intercepted.

A future phase will intercept the tributaries of those tributaries. Ultimately piped sewage infrastructure will be installed in currently unsewered areas, and the interceptor sewers will serve as trunk lines, transmitting waste directly from buildings to treatment plants.

The Delhi Jal Board is in the process of implementing interceptor sewers across the city, including 78 tributary drains that flow into the Najafgarh Drain.

Delhi’s urban waterways are contested territories that serve as corridors for multiple infrastructures. As such, they are sites of intense juxtapositions of jurisdiction and authority. Working in a typical drain corridor can involve coordinating with up to six separate municipal agencies and private interests.

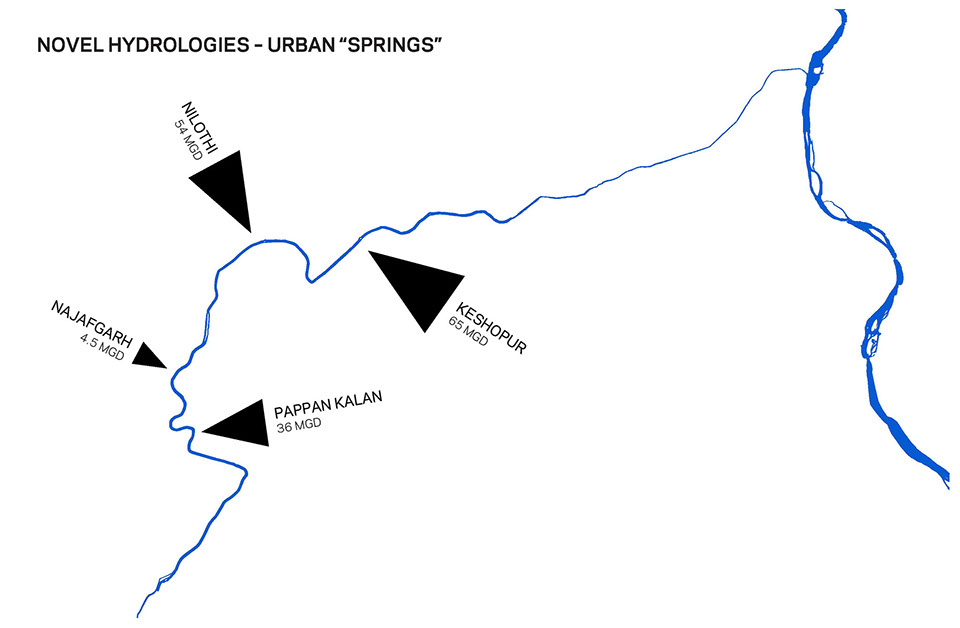

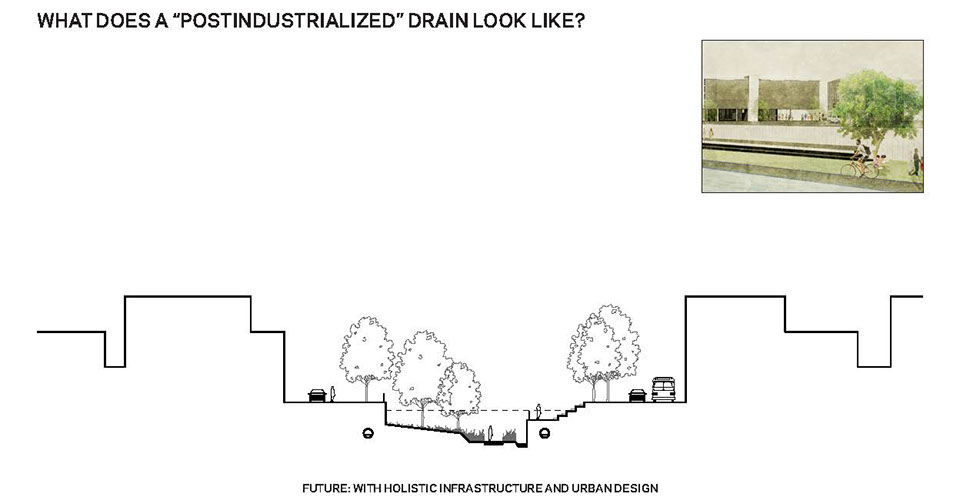

This new condition will dramatically transform the function and character of the drain system. With sewage diverted to piped infrastructure, the subdrains will no longer contribute to the consistent flow of the Najafgarh Drain. Instead, the sewage treatment plants will become new urban “springs,” feeding the Najafgarh, and by extension the Yamuna, with treated effluent.

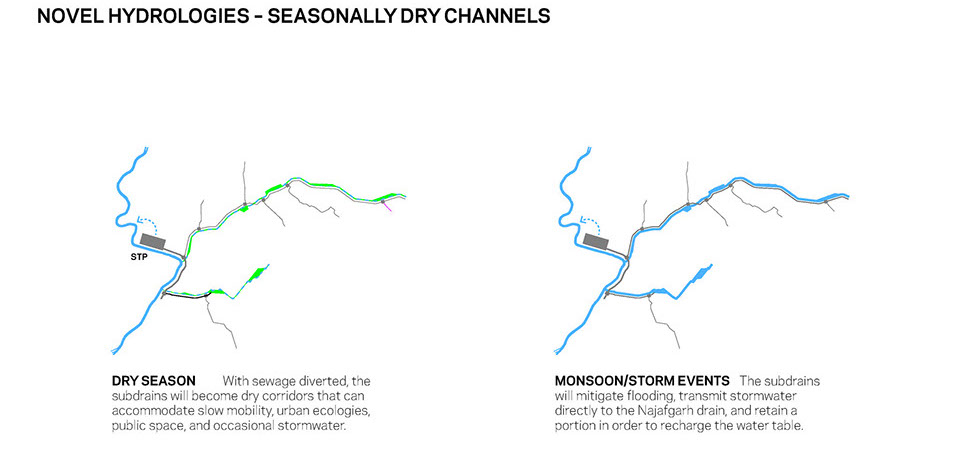

After interceptor implementation, sub-drains will revert to their “natural” function of handling stormwater. Many of them will be dry channels for most of the year. But the annual monsoon and occasional major storm events will require them to be able to handle large volumes of water for short periods of time.

With a holistic approach, this network can become an armature that organizes Delhi’s ecologies, mobilities, and public space.